“The suspension rate was high. MLK lamentably had the highest rate of disciplinary referrals in the entire district,” said Leslie Hu, MLK’s community school coordinator who added that standardized test scores were really low. The principal wanted to incorporate PBL, but knew students were distracted by a lack of basic needs that could not be met at home. Shifting to a community school model helped students with needs like food and medical care, and teachers like Founds were able to invest more time in developing their teaching practice.

Schools aren’t typically designed to offer more than instruction, but by addressing basic needsthey’re finding that students can learn better. Cincinnati Public School Learning Centers, Oakland Unified School District and even Lebron James’ I Promise School in Akron, Ohio, are community schools that lend a helpful framework for closing achievement gaps and improving student outcomes.

“The community school approach is where you take the resources that you think children and families need to really be successful. And you bring all those resources within the school building,” said Dr. Angela Diaz, the director of the Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center.

For example, a community school can help families access health and safety needs by having a medical clinic, dental services, food programs and counselor services on campus.

Some schools, like Buena Vista Horace Mann (BVHM) in San Francisco, have gone so far as to create shelters for unhoused families on campus. Other schools that provide shelter include the Sugar Hill Project in New York and Monterey Peninsula Unified School District.

Community school coordinators find organizations that offer what their families need and partners with them to get access to professionals and funding. At MLK, the school started with food.

Food and nutrition services

Before MLK became a community school, teachers stretched themselves thin trying to help students struggling with trauma or food insecurity. “As a teacher, you’re really positioned to recognize a lot of needs of your students,” said Founds. “You read assignments where it reveals the student is really struggling with their mental health or you know that kid is always coming in hungry.” Founds used to go to Costco and buy granola bars so she would have them on hand for hungry students. When it’s on teachers to fill in the gaps for students, it leads to burnout and takes focus away from academics.

Free and reduced price lunch programs have been around since the 1940s to help families and nearly 30 million children nationwide rely on these programs. Food insecurity continues to affect 10% of kids in the US, leading to lower academic performance and a higher likelihood of behavior issues. When MLK transitioned to a community school model, they expanded student and family support beyond free and low-cost lunch to include a breakfast at school program and meals throughout the day.

Over the past six years, MLK has developed more than 50 partnerships, including organizations like Huckleberry Youth which provide case workers that help families get access to affordable food. “Our teachers don’t need to be as much of a social worker anymore. They don’t need to have their own stash of socks in their closet to give to young people because we have programs for that,” school coordinator Hu told me.

Health and wellness services

MLK distributed a comprehensive health assessment survey with questions about how much students slept and how often they exercised. The survey revealed that many of their students were stressed. “We knew that their health impacts their learning, their ability to stay focused [and] retain information,” said Hu.

The results from the assessments were shared schoolwide and led MLK to partner with the Beacon organization to support student mental health and wellness. Beacon organized community days to celebrate students’ achievements. They also provided push-in services. “If a student’s getting escalated in the class instead of kicking them out of the class or instead of letting them continue to get escalated and disrupt the learning, you make a call and then a support member comes into the classroom to help de-escalate that student,” said Founds, so she’s able to continue teaching the class and other students can learn.

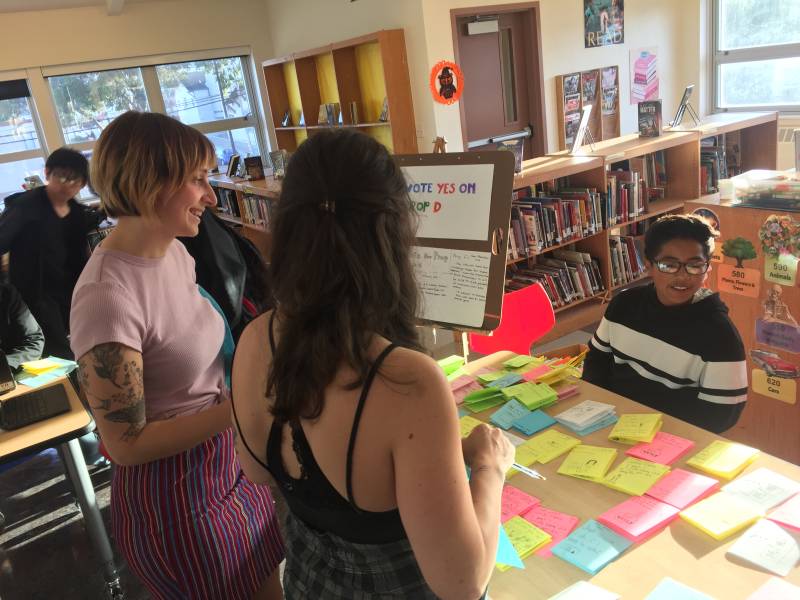

“Students are getting better services,” Founds said. “It’s freeing up time and mental capacity for me to think about, ‘OK, what are the best projects that are going to engage the students and how can I provide differentiated curriculum to support a wide range of learners?’” During an election year , she tasked students with researching a local representative or ballot measure to increase voter engagement for a school wide event. “We were able to invite local candidates, local supervisors and a lot of them actually showed up to that election night. And so then it goes from just being like, ‘Oh, you did your report’ to, ‘Oh, you’re actually meeting people who could be your future representative.’”

Using the community school model went hand-in-hand with PBL, said Founds. “One supports the other.” Students had better academic performance with their Math and English Language Arts test scores, which were improved by nine percent and outpaced the rest of the district. And MLK’s teacher turnover, which in previous years had been as high as 61%, has improved.

Housing and shelter

Each community school is different because the services they offer depend on the needs in the community. Buena Vista Horace Mann is a K-8 Spanish immersion school community in San Francisco. With a large population of recent immigrants and low income students, BVHM used the community school model to get them essential food, health care and mental health services. They already had partnerships with community mental health agencies and the local food bank, but they noticed that housing was an issue for many students’ families.

“We were seeing a ton of our families in shelters or homeless or in cars,” said community school coordinator Nick Chandler, who recalled one family asking him, “Can we just stay here tonight in your building?”

1 in 5 students in California have experienced homelessness with numbers growing due to unemployment in the wake of the pandemic. Latino immigrants experience a higher risk of housing instability and more barriers to getting help, including language barriers, according to a MacArthur Foundation report. There were not enough beds for families at local shelters and many Latino caregivers didn’t feel comfortable going to the shelter.

Students experiencing homelessness are more likely to be chronically absent and less likely to complete high school. “The brain is not going to absorb the best teacher in the world’s information if we’re not addressing these underlying challenges,” said Chandler. So Chandler and school leaders proposed turning their school gym into an emergency shelter for families.

They had schoolwide meetings to discuss the possibilities before they opened up this service four years ago. Latino and low-income families, who previously hadn’t spoken up much, supported the shelter, while affluent families, who were often white, were against it. “That power dynamic that exists in the community reflects the national power dynamic,” said Chandler about the community meeting. “Folks with privilege tend to have the control and influence and steer. This upset that balance.”

“There was a stigma about who homeless people are. When you think of a homeless person, you think about addiction or violence. We didn’t want that near our kids,” said Maria Rodriguez in Spanish. She has three kids who go to BVHM.

To address concerns, BVHM made a website listing every question asked at the meeting and how they were answered. Around 200 questions were shared and answered in English and Spanish. In response to questions about sanitation, BVHM assured families that the gym would be cleaned each morning. Those who were worried about safety were told that there would be a security guard on duty during the hours the shelter was open. Parents were also assured that running the space would not cost the school additional money.

“As more meetings were held, we found out more about the rules for the space and how the shelter would be supporting families. I felt more calm after they said they’d be cleaning it up after families stayed the night and that kids would be able to use the gym again during the day,” said Rodriguez in Spanish.

BVHM decided to convert their gym into a shelter that operates from 7 pm to 7 am and operates in partnership with a local housing organization. “Our families have a place to be so that they can rest so that when [students] come to school, we know they have a place to sleep,” said Chandler. Up to 20 families are able to stay in the shelter at once. Families must have a student enrolled in the San Francisco Unified School District. This is the third year of their “stay over” shelter program.

After the shelter opened, some families left the school. “We did have a shift in our population, so we have less white students now than we did five years ago. And yet our enrollment has maintained and increased,” said Chandler.

For the parents that stayed, this process of discussing the shelter built trust between the families and the school. Parents felt that BVHM was committed to filling in the gaps and becoming a safety net when families navigated hard times.

“When I think about what a community school is, I don’t think every community school needs a homeless shelter,” said Chandler. “I think that willingness to open that space and to let families dictate the needs of the community and use that information to advocate for resources is what a community school is.”

From free and reduced price lunches to after school programs to buses, schools have always evolved to give assistance to families who need extra support. Community schools and their focus on the whole child are the next step in schools expanding to meet families needs. Kids are required to attend schools, making them an accessible place to provide resources for caregivers with crammed schedules while continuing to get students what they need to learn.