What is wrong with grades?

Instructors and students have different ideas about what grades are supposed to measure: Should they be about how much students have learned? How much work they have completed? How well they have mastered the subject? (Arguably, they measure none of these well.) Grades can perpetuate bias, inequalities, and injustice, reduce student motivation and willingness to challenge themselves, and add enormous administrative burdens. No wonder many students and faculty dislike grades!

However, grades are not going away as a tool for evaluation, sorting, and gatekeeping by institutions and employers, and as a measure of success by students. But there is literature on how to adapt the grading process to avoid the drawbacks above, and improve student motivation and engagement, as well as instructor satisfaction. They go by names such as curving, ungrading, contract grading, and specifications grading.

In 2022, I experimented with a combination of specifications grading and self-grading that promised to more fairly measure performance, increase engagement, and promote metacognition. It produced insights into how students measure and view their own performance. It also helped me to reduce bias and noise (unwanted random variability) in my final grades.

Specifications grading

To grade as objectively and as fairly as possible, the course grade was based on a measure of productivity. Students earned points for every assignment that they completed to minimum specifications and for quizzes. Minimum specifications can motivate overwhelmed students by increasing expectancy—giving students the confidence that they can complete the task. Students may revise and resubmit an assignment that does not meet minimum specifications for full credit. The ability to revise an assignment supports a growth mindset because it suggests that effort produces learning. This supports student risk-taking.

The specification reduces the administrative burden of calculating (misleadingly) precise scores and partial credit for each assignment. This leaves more time to provide meaningful feedback, which can be more motivating and meaningful than a numerical value.

Still, even specifications grading has weaknesses. Implicit bias may lead instructors to interpret requirements differently for different students systematically and non-consciously. Noise can also be a factor. Personally, my grading rigor can vary randomly due to unrelated factors such as mood, weather, and distractions. On average, I may also be a harder or easier grader than other professors with respect to specific factors such as grammar, math, reasoning, or content. Further, many people believe grades measure more than just the work completed.

Student self-grading

The second component of the final grade, student self-grading, helps address some of these issues. Students have insight into the effort they have invested, the learning they have achieved, the hurdles they have cleared, and the personal goals they have attained. Further, they have experienced how other instructors at the college grade; a student’s self-grades should be a proxy for the average level of grading rigor at the college, which may be opaque to any individual instructor.[1]

Self-grading proceeds in three steps:

At the beginning of the semester, students complete a form in which they set SMART goals in six categories:

- Skills and knowledge gained

- Work completed (points earned)

- Quiz scores (average, trend)

- Obstacles overcome

- Support you’ve offered classmates

- Participation in office hours, live classes, and events

These criteria identify and motivate focus on many dimensions of learning that grades are supposed to measure but are hard to assess using traditional tools. They support motivators such as growth mindset (1-4) and a sense of belonging (5-6).[2]

In the middle of the semester, students grade themselves on each criterion, providing evidence for each. They also provide an overall grade. I provide feedback on points of agreement and divergence.

At the end of the semester, students repeat this process.

Self-grading supports metacognition

Many entries show evidence of self-perceptiveness and metacognition.

- “I [now] know which tool to avoid and which to use in decision-making.”

- “I am more focused and more confident.”

- “I watch [sic] extra videos that helped me.”

- “I started off strong but with my other course work and family life, I faltered.”

- “I had [sic] been able to learn a vast amount of knowledge…”

- “I learned how to manage finances when it comes to investments, to even teaching my family once in awhile [sic] since they seem to be invested in the course as well.”

- “… the only thing that is hard constantly is the excel, I tend to put information where it’s not meant to be. However, I had private group call…I started to get the hang of it.”

- “I have taken tools from this class and implemented them into my work life”

Self-grading adds quantitative information

Students’ average self-grades were close to the average productivity measure (88.0 vs. 85.5). However, the top quartile productive students underestimated their work (91.7 vs 99.4). While the bottom quartile in productivity overestimated their work (80.8 vs. 67.1).

Perhaps less productive students had poor awareness of their work quantity and quality and weak metacognition, an example of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Or perhaps they experienced easier grading in other classes and expected the same in my class. They could also be measuring obstacles they overcame or learning that I did not measure. Possibly, the higher performers underestimated their achievements due to imposter syndrome or a better appreciation of gaps in their knowledge.

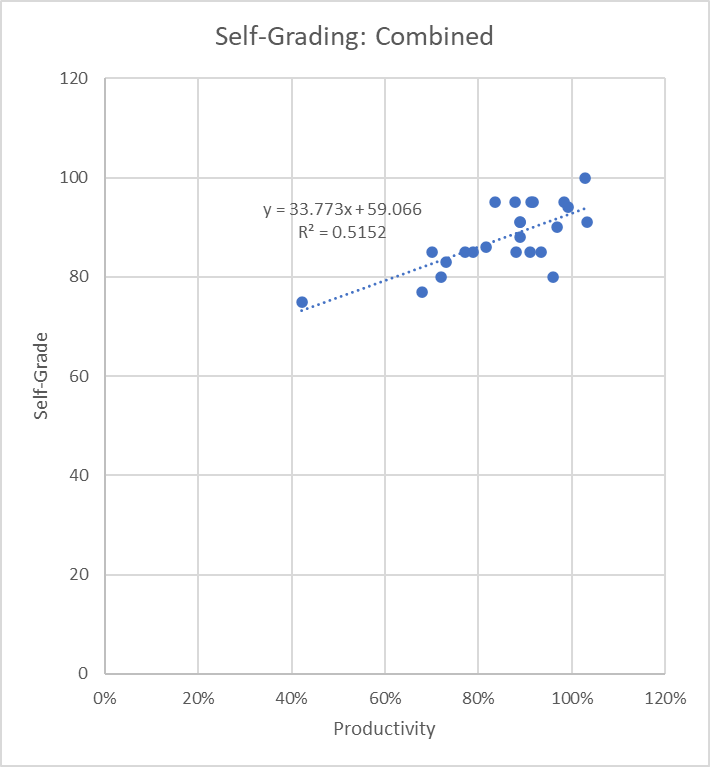

The chart below shows the relationship between productivity and students’ self-grades. The two measures are correlated. However, student self-grades are remarkably insensitive to work completed. Every ten percent of work completed translates into only 3.4 points of higher self-grade. It also implies that a student who did zero work would give themselves a virtually passing grade of 59.1. Maybe students value successfully completing the class.

Using self-grading to “curve” final grades

I used the relationship in the chart above to help create a grading “curve,” a formula to convert productivity scores into final grades. Because not all students completed the self-assessment, and their own measures are subject to bias and noise, I calculated a best-fit line between productivity (x) and self-grade (y). The final grade was the average of the productivity grade and the predicted self-grade, adjusted to ensure that high performers were not penalized. Mathematically, the final grade was 70x+30.

The effect is to add about 15 points to less productive students’ grades, and progressively less to higher performing students. For example, a student earning 50% of the available points, would have a predicted self-grade of 70*50%+30=65. A student earning 85% of the available points would receive a one-half grade letter benefit.

Student feedback

Student survey responses suggest that collaborative grading is working for students, albeit with some tweaks needed. All eight students who responded said they thought their final grade was “just right.” They said their grades ranged from C+ to A. Three of the four students who completed the goal-setting and self-grading exercise said it motivated them to set more ambitious goals and to achieve those goals. Seven said the policy that allowed them to revise work encouraged them to do more than the minimum required; however, two said the policy confused or irritated them.

A work in progress

Hybrid grading can create a course that is easier to pass (lowering DFW rates) without sacrificing rigor for highly productive students. It incorporates students’ own information about their learning, creating a more robust, valid, and fair measure. It helps calibrate course grading rigor with others in the college. Additionally, goal-setting and self-assessment appear to motivate students to engage, work harder, and build metacognitive skills. In the future, I will experiment with sharing the formula with students to see how this affects performance. It would be interesting to compare self-grading results over time, in online versus in-person classes, and with other instructors.

Brett Whysel is a full-time lecturer in the Business Management Department at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. Whysel teaches managerial decision-making, introduction to finance, and financial management all asynchronously and in-person. He has been teaching at BMCC since 2019. Prior to that he was an adjunct lecturer at the City College of New York in the MPA program. Whysel is the co-founder of Decision Fish LLC, which creates social impact by helping people make better decisions with financial wellness programs, consulting, public speaking, and coaching. Before transitioning to higher education, he had a 27-year career in public finance investment banking. Whysel has a master’s degree in philosophy from Columbia University and a bachelor’s degree in managerial economics and French from Carnegie Mellon University. He has earned three teaching certificates from ACUE.

References:

[1] D, F, and Withdrawal (DFW) rates may help with calibrating grades.

[2] Recently, I have added: “Applied new skills/knowledge in life.” This will get at a third motivator: relevance.

Post Views: 11